Paper Rundown: Online List Labeling with Predictions

Algorithms with Predictions?

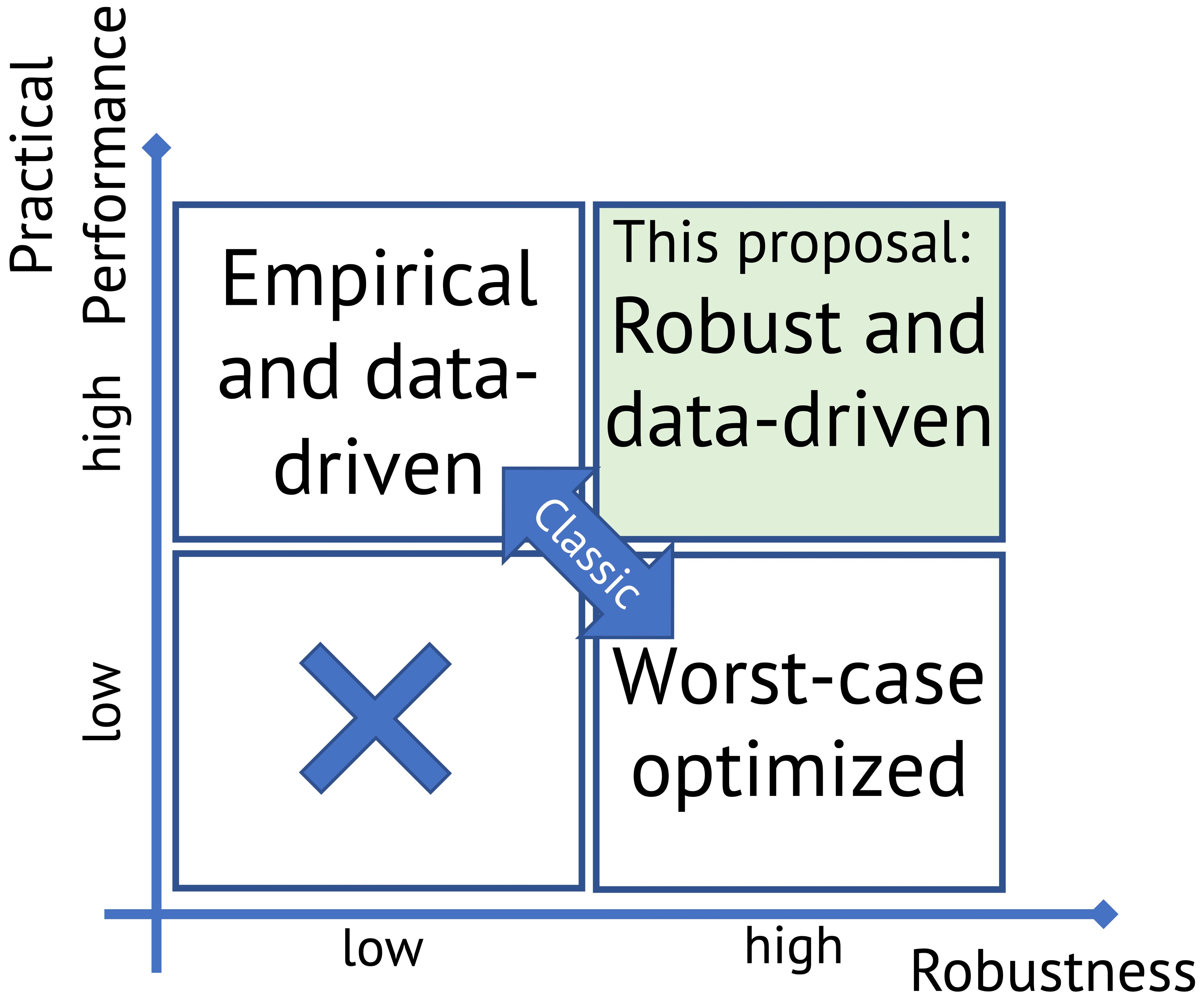

As it turns out, most algorithms and data structures can benefit from predictions. These predictions can come in many forms — a neural network trained on historical input data, or really any machine learning model capable of anticipating future inputs. The goal of this approach is to design an algorithm (or data structure) that leverages these predictions as much as possible, while still matching the expected performance and behavior of state-of-the-art alternatives that do not use predictions.

Online List Labeling

The goal for this paper was to create a data structure (they called it LearnedLLA) to optimally leverage input predictions to achieve an improvement over the List Labeling Array.

(If you need a refresher on the classical LLA model or don't know what LLA means 😃, check my blog post on LLAs here.)

Prediction Model

The authors made the assumption that for every item arriving in the LearnedLLA, we would get a predicted rank . Define the rank estimation error of an element , as:

Then define as the maximal error of all the predictions.

LearnedLLA

LearnedLLA, like the classical LLA, contains an array of size for some ( in the case of LearnedLLA), and a calibrator tree of height . The twist? Each node in the calibrator tree could hold its own LLA — which can be any implementation you like, from the classical to state-of-the-art with amortized cost per insertion.

A closer look on LearnedLLA

At all times, a LearnedLLA instance with capacity is split into partitions , where , such that each partition is handled by its own black-box LLA, and for any and , if then . This structure is reflected in LearnedLLA's calibrator tree. Each node in the tree has a set of assigned ranks and assigned slots, with all ranks divided equally among the nodes at the same height. The root is responsible for slots and all ranks , its left child is responsible for ranks , and its right child is responsible for ranks , and so on. The leaves of the calibrator tree contain nodes, each one has slots and responsible for a rank (assuming is a power of two). To put this more precisly, the th node at height has assigned ranks

,

and assigned slots

.

Each node in the calibrator tree either corresponds to an LLA — we call these nodes actual LLAs — or it does not, in which case we call them potential LLAs, as they could become LLAs during runtime. It's useful to think of all other nodes in T to be "potential" LLAs. Each root to leaf path could only have one and only one actual LLA. At initialization, all leaves of corrospond to actual LLAs. We define to be the number of ranks assigned to an actual LLA , and let be the number of elements present in an actual LLA .

Insertion

Insertion is fairly simple. To insert some element with a predicted rank :

- Find and , where and are the actual LLAs that hold 's predecessor and successor, respectively.

- Find , where is the actual LLA responsible for rank .

- Compute i where:

- If would exceed the threshold density of , merge it with its sibling LLA in the calibrator tree, and call

initon the potential LLA at their parent. Otherwise, callinserton .

Main Results

Insertion Cost

For arbitrary predictions, using the classical LLA model as a black-box, they proved that their insertion algorithm acheives a amoritzed cost per insertion.

-

When predictions are perfect (i.e., each predicted rank exactly matches the true target position), the insertion cost is constant — .

-

When predictions are poor — specifically, if at least one prediction is maximally wrong (as far from the target as possible) — the insertion cost falls back to , matching the complexity of traditional, non-predictive LLA.

More generally, for any LLA insertion algorithm with an amortized cost of (where is an admissible "reasonable" list labeling cost function), plugging it into the LearnedLLA model as a black box yields an amortized insertion cost of .

They took it a step further, and proved a more powerful result:

- For prediction errors that are sampled from an unknown distribution with mean , and variance , their algorithm acheives an expected cost of . That means for distributions with constant mean and variance.

Optimality

They claim that their algorithm is optimal. Following their prediction model, they prove that any deterministic list labeling algorithm must acheive .

Open Questions.

Well, there is a big problem they don't highlight in their paper: If only one prediction was maximally bad, and the rest were perfect, their algorithm will still incur . I will explain this in good detail in a later post!!

References

-

McCauley, S., Moseley, B., Niaparast, A., & Singh, S. (2023). Online List Labeling with Predictions. arXiv:2305.10536

-

Bender, Michael A., Alex Conway, Martín Farach-Colton, Hanna Komlós, Michal Koucký, William Kuszmaul, and Michael Saks. Nearly Optimal List Labeling. arXiv, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.00807

-

Bender, M. A., Demaine, E. D., & Farach-Colton, M. (2000). Cache-oblivious B-trees. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (pp. 399–409). IEEE.